STORIES FROM PAFA

Landscapes Are Not Neutral, but Rather Perspectives of Power

The Muhheakunnuk and Tool-pay Hok Ing rivers are the focus of PAFA’s current museum exhibition. But most people are more familiar with these waters using the names Hudson and Schuylkill, respectively.

“From the Schuylkill to the Hudson: Landscapes of the Early American Republic” is an exploration of landscape painting in the United States before the Hudson River School. It is also a tribute to the people who inhabited the land before there was the United States of America.

The Schuylkill and Hudson Rivers and the city of Philadelphia are situated in the homelands of the Lenape people. The waterways are most well-known by their current Euro-American names which are how they are referenced in From the Schuylkill to the Hudson.

“Some visitors to PAFA may have heard of the contemporary “museums are not neutral” social justice movement—well landscapes are certainly not neutral either,” said Dr. Anna O. Marley, PAFA’s Curator of Historical American Art. “These landscapes are beautiful and I hope people enjoy looking at them and enjoy the installation, but I also want them to understand landscape paintings are a construction of empire.”

The rivers surrounding Philadelphia and the Hudson in New York have long and rich traditions as part of communities other than those depicted by settler-colonial artists.

Marley encourages museum visitors to look for the Native American presence in the exhibition, but she adds that many of the Native Americans that are included in these landscapes are not accurate representations of the Lenape or Iroquois people.

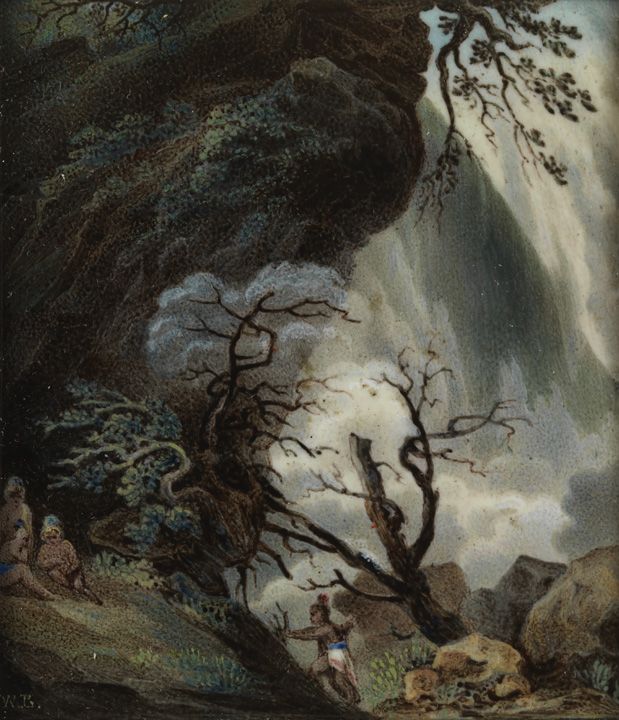

In a miniature painting of Niagara Falls by William Russell Birch, a family of Native Americans figures is present. But Marley said Falls of Niagara from 1827 is not historically accurate.

“The Native Americans pictured are very stylized, and they are not wearing identifiable tribal clothing,” Marley said. “By the mid-1820s, Niagara Falls was a tourist destination, and the Iroquois League of Nations, that had once called Niagara home, had been displaced by US imperial policy west of the Northwest Territory line of the Ohio River.”

Alongside the Birch painting is Cataract of Niagara by William Byrne. The print is based on a military drawing from the 1760s by Lt. William Pierie. At that time Fort Niagara was a central location of the wars between the French and the English and Iroquois League of Nations in the period before the American Revolution.

Native Americans, who would have inhabited Niagara at the time, have been replaced by a European couple walking with a parasol.

“In the period when the Iroquois were probably still living in their ancestral lands, this British military artist has placed picturesque tourists in the painting,” Marley said.

Pierie was a trained topographic military artist was trained at the Royal Military Academy in London. His drawing and the subsequent print by Byrne are aesthetically pleasing but should also be recognized as colonial and imperial tools of both measurement and control.

Our curatorial team is encouraging visitors to ask themselves whose perspective is being captured and whose land you see when looking at the landscapes in this exhibition.

Join us for two upcoming events to acknowledge and discuss the missing stories and difficult narratives embedded in early American landscape traditions of representation;

- We Are The Seeds: Panel and Performance, Saturday, November 23, 2019

- Point of View Speaker Series: Public Dialogues, Landscapes Are Not Neutral, Saturday, December 7, 2019

“From the Schuylkill to the Hudson: Landscapes of the Early American Republic” is on view through December 29, 2019.

We're so excited you're planning to visit PAFA!

Make time for art — visit us Thursday to Sunday.

Before reserving your tickets, please review helpful information about museum hours, accessibility, building access, and special admission programs.

If you have any questions, feel free to reach out to us at visitorservices@pafa.org — we’d love to help!